But anyone who has read Schulz's comics knows that he can be satirical and even brutal about religion, especially his own. (I highly recommend his comics created for the Christian magazine Youth, a criticism of religion from within its own walls.) The most famous example of this satire is his use of the Great Pumpkin, a holiday deity only believed in by Linus.

One day I'd like to write about every appearance of the Great Pumpkin in the entire run of the comics, but for now the TV special It's the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown will do.

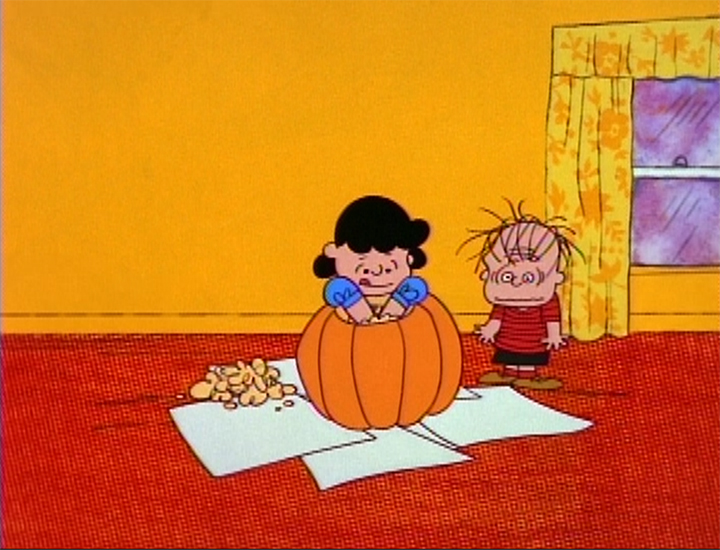

At the beginning of the special, Linus demonstrates his belief in animism when he is horrified that Lucy has stabbed a pumpkin to death and removed its guts in order to make a jack-o-lantern. ("You didn't tell me you were gonna kill it!") Linus's horror is further explained when we later find out about his belief in the Great Pumpkin, Lucy's now-dead pumpkin being -- presumably -- one of its earthly avatars.

Linus, of course, is already at this point in Peanuts history (this is 1966) known by fans as the religious scholar among the Peanuts characters. His knowledge of the Bible, his overall intelligence, and his generally kind nature makes him one of the more positive characters. But he also clings to a security blanket and sucks his thumb. And, it turns out, he is clueless enough to have somehow conflated Halloween and Christmas, pumpkins and Santa Claus.

The mythology of the Great Pumpkin is that he arrives on Halloween night, rising out of the pumpkin patch to bring presents to all the boys and girls of the world. He knows which kids have been good and bad. Most of this is Santa, of course, and Linus at one point asks if the children are joining him to sing "pumpkin carols." This simple joke was probably the main reason for Schulz's invention of this idea.

As for Linus inventing the Great Pumpkin, who knows how he came up with it? His child brain (in his case, highly creative and supremely innocent) probably just has crossed wires, not a surprise since Christmas creeps in during Halloween anyway (something that Schulz satirized in other specials and comics long before this phenomenon became truly out of control). So Linus is the only one who believes and keeps the faith, giving us insight into what our own religions look like to people who don't follow them.

Charlie Brown tells Linus, "You must be crazy. When are you going to stop believing in something that isn't true?" Linus answers: "When you stop believing in that fellow with the red suit and the white beard who goes 'Ho ho ho' " and walks away. The first true nod to this TV special being a religious satire appears at this point, when Charlie Brown says (to the audience) "We are obviously separated by denominational differences."

The point, of course, is that Santa and the Great Pumpkin are essentially identical. Linus is no more objectively crazy than Charlie Brown. The only difference is that the majority of children Charlie Brown's age believe in Santa Claus. And, as we know, the perception of sanity has less to do with what is actual and more to do with what is "normal." Belief in Santa (though he doesn't exist) is widespread and "sane," while belief in the Great Pumpkin (who also doesn't exist) is considered insane because it is not a belief held by the majority.

Linus also doesn't have the luxury of having an omnipresent deity. Santa Claus is -- almost literally -- everywhere, at least at Christmastime. You can't open your eyes without seeing him somewhere--some representation of him. Even real life versions of Santa are at every mall. You can sit in his lap! And, of course, those presents he promised you are actually there Christmas morning, with the additional evidence of an empty glass of milk and cookie crumbs. No actual religion could ever provide for us this level of "reality." If it did, there would be no reason to doubt them.

A common observation these days is that if you want to understand how an atheist views your religion (if you're a Christian, for example), just look at a religion that you don't subscribe to, especially a newer one like Scientology. In this scenario, "Charlie Brown" is saying Linus is crazy for believing in Xenu and body thetans and E-meters, but "Linus" could counter by saying that Charlie Brown is crazy for believing in Satan and the immortal soul and rosary beads. (Of course, even Scientology has many followers. With the Great Pumpkin, the number of believers is only one little boy.)

So what is Schulz really up to so far? Is he attempting to have us question our religious beliefs? Is he making us realize that we sound just as crazy as Linus by believing in the invisible things we believe in? Yes and no, I think.

I know that Schulz likes to find humor not necessarily in religion itself but in the human behaviors of religious people. He is definitely making fun of how we believe, possibly how even he believes. If you question a believer long enough, the answer eventually comes down to something not much better than "I just believe that what I believe is true." In one comic strip, Schulz has Snoopy writing a book on theology called Has It Ever Occurred To You That You Might Be Wrong?

This title was also the punch line in a later strip involving the children being sent to a fundamentalist church camp. Camp leaders had been scaring some of the kids by saying it was the "last days" and other religious nonsense. Linus spoke up and asked the leaders this question. It was a glorious moment.

On the other hand, I don't think that Schulz is -- as some have suggested -- going full-blown agnostic on us. Schulz probably believed in God until the day he died, but he certainly was a questioner and studier and he hated anyone who claimed to have all of "the truth." Although he endeared himself to many Christians for his use of his religion in his strips and television specials, he also alienated many by calling their beliefs into question and using these beliefs as a source of humor.

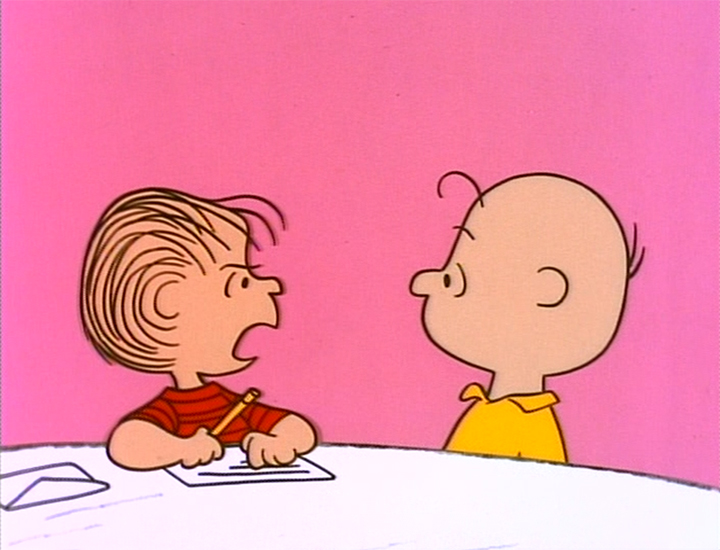

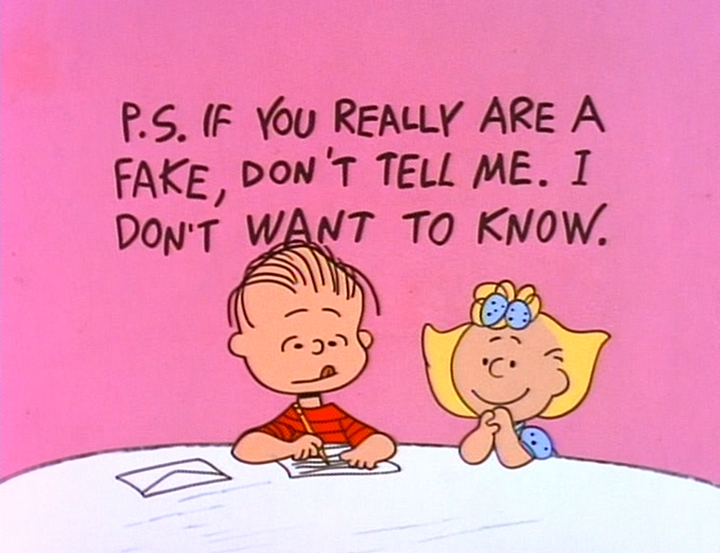

One of the best lines in the show concerning belief is when Linus is writing a letter to the Great Pumpkin. He says, "Everyone tells me you are a fake, but I believe in you. P.S. If you really are a fake, don't tell me. I don't want to know." So, when it comes to the Great Pumpkin, Linus is a fanatic. He refuses to listen to anything suggesting that the Great Pumpkin isn't real--even from the Great Pumpkin himself (a hilarious bit of illogic). Since there is no evidence at all for the Great Pumpkin's existence, belief is all Linus has.

Belief and "faith," of course, are two highly-valued possessions in religious culture. That's why they show up so often as one-word home decorations. When we're talking about either God or Santa Claus, belief is what our culture has decided is the most important thing. To see it ridiculed like this (especially by a believer) should be off-putting. You can see why some Christians assumed Schulz was an atheist. Compared to those who value belief above all and who find it sacrilegious to question those beliefs, he may as well have been.

Now we move into the part of the show where Linus attempts to woo a potential convert, Sally. She, of course, is interested in Linus romantically. He's older and she regards everything he says as intelligent. For her, Linus is the perfect charismatic figure, so it doesn't take too much for her to consider the possibility of Linus's belief. "Maybe there is a Great Pumpkin" she tells the other kids.

Where God is concerned, nearly everyone around you could be a potential Linus figure (from Sally's point of view) from the day you are born. Everyone is older, wiser, someone you respect and love. If your parents or ministers or teachers or president had told you that the Great Pumpkin was real when you were Sally's age, you would have believed them. If they had told you to sit in the pumpkin patch with them on Halloween night, you would have done so unquestioningly, especially since most of the world would be doing the same. You'd probably still be doing it now. If you managed to abandon those beliefs, you'd have millions judging you for not sitting in a pumpkin patch and for not believing.

The Great Pumpkin, God: it's all the same.

This is where Sally's story becomes a sad one. Because this is the first year she is old enough to able to fully participate in Halloween. She can go trick-or-treating, and she can go to the Halloween party with the other kids. But her love for Linus -- and her willingness to believe that the Great Pumpkin may exist -- makes her sit in the pumpkin patch with him instead. She still has her doubts, causing Linus to say to her, "I thought little girls always believed everything that was told to them. I thought little girls were innocent and trusting." (This, of course, is what is counted upon when belief without evidence is concerned.) To her credit, Sally says, "Welcome to the twentieth century," a great comment on how -- as time marches on -- this sort of blind faith disappears.

Linus turns on the magic for Sally at this point, telling her about the sincerity of his pumpkin patch and how the Great Pumpkin respects sincerity. (These days, one can't help but think of the legal phrase "sincerely held religious beliefs" and how it allows businesses to discriminate.) He tells Sally that she'll be able to see the Great Pumpkin "with [her] own eyes." He tells her this in spite of the fact that he's never seen the Great Pumpkin with his own eyes, even though he's sat out here and waited before. The other kids say that "every year" he misses trick-or-treat and the party, which implies that this has happened at least twice, maybe almost every year of his young life.

Linus is the "man of God" getting us to sit in a church pew Sunday after Sunday, missing life itself because Jesus could show up at any time if we just believe. The minister isn't trying to trick anyone. He truly believes it himself; it is a sincerely held belief. His church is "nothing but sincerity as far as the eye can see." But there isn't anything actually there, nothing actually coming. Everyone is waiting for Godot.

This doesn't deny the potential beauty of the church service or of the pumpkin patch. There is a moment in the special, when Linus is waxing poetic, when one might envy Sally, when one might wish to be there with charming, sincere Linus in the pumpkin patch: the enormously full moon behind them, stars shining, a slight fog, the stillness of the night... well away from the blabbering of Lucy and the gang. No candy to rot your teeth. No rocks in your bag. The pumpkin patch can save you lots of heartache, and so can the church. The church, undeniably, can conjure up what feels like magic. The anticipation for what is promised can be overwhelming and seem to give life a higher purpose.

Ridicule -- cruel as it may be -- is often exactly what we need to break this spell. The Peanuts gang is always up for some good ridicule, and it is at this point that the other children, having finished their trick-or-treating and who are heading toward the party, show up at the pumpkin patch to mock Linus (and Sally). "What a way to spend Halloween!" one says. Sally, now having to resort to anger and defense like Linus (a pumpkin apologist), says to them, "You think you're so smart. Just wait until the Great Pumpkin comes. He'll be here. You can bet on that. Linus knows what he's talking about. Linus knows what he's doing." But then, when they leave, Sally angrily turns to Linus and says, "All right, where is he?"

As someone being sucked into the religious spell but not yet under it completely, Sally is willing to give the benefit of the doubt, but she reserves her right to be skeptical. She needs some evidence, not just faith, especially if everyone is going to be making fun of her.

It is at this point that the Great Pumpkin "arrives" for Linus, in the form of Snoopy in silhouette. When you're so willing to believe, an appearance of anything that remotely resembles what you're looking for can be mistaken for the real thing. We see examples of this all the time, from the ridiculous (Jesus appearing in toast) to the strange (Virgin Mary statues crying or bleeding) to the coincidental ("answered" prayers of things that were going to happen anyway). Plain old human emotion can also be mistaken for God, and Linus experiences a sort of religious ecstasy when he thinks he sees the Great Pumpkin and faints.

But clear-headed Sally sees the truth, and it's the final straw for her. If Linus can mistake a beagle for the Great Pumpkin, it's certain that he's wrong and that she's missed her opportunity to participate in the actual pleasures of life. Her angry tirade against Linus (and herself) is worth quoting in full. It's a lovely speech, and could bring tears to the eyes those who have wasted a good deal of their lives following an imaginary dream:

"I was robbed! I spent the whole night waiting for the Great Pumpkin when I could have been out for tricks or treats. Halloween is over and I missed it! You blockhead! You kept me up all night waiting for the Great Pumpkin! And all that came was a beagle! I didn't get a chance to go out for tricks or treats. And it was all your fault! I'll sue! What a fool I was! I could have had candy apples and gum and cookies and money and all sorts of things! But no! I had to listen to you, you blockhead! What a fool I was! Trick or treats come only once a year, and I miss it by sitting in a pumpkin patch with a blockhead! You owe me restitution!"

For Sally, tricks or treats come once a year. For us, we only get one life. "What a fool I was!" is a common sentiment for those who have missed out on the full participation in secular life itself because they've been too busy listening to and following religious blockheads. All those Sunday mornings that could have been spent having real activities with family or friends that didn't involve sitting on a bench listening to a repetitive and fantasy-based message. All of that misplaced hatred for people God supposedly finds abominable. All of that body shame and guilt about sex. All that time you were told you were born full of sin and believed it and acted accordingly. All those Bible verses memorized instead of devoting that brainpower to something more meaningful. "What a fool I was!" indeed.

Of course, Linus will never see beyond his own delusion. As Sally leaves, Linus says, "Hey, aren't you going to wait and greet the Great Pumpkin? Huh? It won't be long now." No, really: Jesus is coming soon. Any day now! Can't you see the writing on the wall? This is the end times, people! You've come too far to turn back now!

Linus continues: "If the Great Pumpkin comes, I'll still put in a good word for you. Good grief, I said 'if'! I mean when he comes. I'm doomed. One little slip like that can cause the Great Pumpkin to pass you by." This, too, sounds familiar. It isn't enough to simply believe in Jesus. You have to believe with all your heart. You can't doubt for a second. There's a constant fear of him passing you by, of being "left behind." Because, apparently, Jesus and God are like that. You can be the sweetest kid in the world and do everything right, but if you make some slip like saying God's name with a bad attitude or if you say "Happy holidays" instead of "Merry Christmas" or if you doubt for a second that anyone is actually hearing your prayers, God has every right to ignore you forever.

At this point, like Jesus himself crying out his last words on the cross when God has abandoned him, Linus yells to the sky, "Oh, Great Pumpkin, where are you?"

Linus does all he can do, which is to sleep out in the cold, shivering under his security blanket. It is up to his "mean" sister Lucy to take care of him (after spending a night embarrassing herself by asking for extra candy for her brother, who didn't deserve it). She brings him inside, takes off his shoes, puts him in bed, and tucks him in. She cleans up his religious mess. Somebody has to live in the real world, and sometimes it is the crabby realist who actually gets things done.

After all this, Linus hasn't learned his lesson. When Charlie Brown suggests (innocently) that Linus shouldn't feel so bad for missing Halloween because he has done some stupid things in his life, too, Linus goes full-blown angry apologist again: "Stupid?! What do you mean: stupid?!" Appropriately, the special ends not with Linus learning anything but with Linus hanging on tighter and more desperately than ever to his baseless beliefs.

The Great Pumpkin is a belief of one fictional character, but we know what it's like when this level of belief is spread to millions. We know what it would be like if, say, Peppermint Patty had an opposing belief, maybe about the Omnipresent Specter, the real (to her) deity that comes every Halloween. We know what it would be like if Schroeder also believed in the Great Pumpkin but thought that believers were supposed to sacrifice a squash to him instead of waiting in a pumpkin patch. We know what wars between these various factions would look like. We know what it would look like for politicians to declare their belief in the Great Pumpkin to even get elected (the opposite of what happened in You're Not Elected, Charlie Brown, when Linus's mention of the Great Pumpkin during a campaign speech cost him several votes). We know exactly what all of these absurdities look like in the real world, because we live them every day.

Of course, in writing all of this, I'm ignoring Linus's wisdom when he says, "There are three things I have learned never to discuss with people: religion, politics, and The Great Pumpkin."

No comments:

Post a Comment