I first read William Blake in high school when I was about sixteen years old: Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience. I liked those, but I started really liking Blake when I chose to do my eleventh grade research paper on his life and works. The more I found out about him, the more weirdly familiar he seemed to me, until I eventually started flattering myself with the thought that I must have been William Blake in a previous life (something that still crosses my mind each time I read him).

I first read William Blake in high school when I was about sixteen years old: Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience. I liked those, but I started really liking Blake when I chose to do my eleventh grade research paper on his life and works. The more I found out about him, the more weirdly familiar he seemed to me, until I eventually started flattering myself with the thought that I must have been William Blake in a previous life (something that still crosses my mind each time I read him).I was intrigued by Blake as a mystic, his having visions of his dead brother and of angels, of staring at a knot in a piece of wood until he became scared of it, etc. I've never had strong visions or dreams about anything (unless you count my occasional sleep paralysis), but I like the concept of seeing things that aren't there--or specifically, seeing differently the things that are there. I think I do this different-seeing a little, though sometimes I simply see nothing where everyone else sees something. Lots of this world is invisible to me.

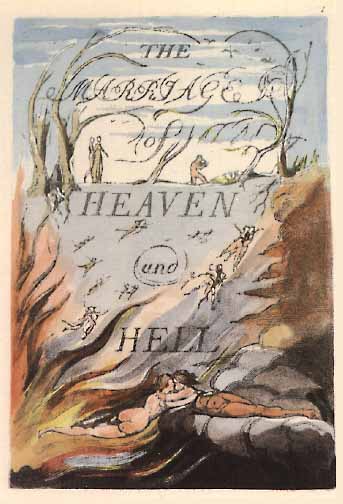

I was also intrigued by Blake as a visual artist. He was just as much a drawer, painter, engraver, etc. as he was a writer, and I loved the way he combined the two on the same page (or, in his case, engraved plate). This is how I got my start as a writer, too: writing words to tell stories about my pictures (and not the other way around). Like a lot of my favorite storytellers (C.S. Lewis and David Lynch to name two), the images came first. He also produced everything himself, rather than going to a traditional publisher, creating his books indie rock style, which is way that I've approached most of my art (especially my music), often from necessity but also because I like the freedom.

I became especially interested in Blake's prophetic books, though I didn't begin reading them properly until recently. As a teenager, I liked reading about them, but I must have felt (after glancing at the works themselves) that they were too much to undertake at that young age, so I put them off until later. Every time I read them now, that familiarity hits me again. They get me excited, and they also make me laugh.

I will probably eventually create posts for most of Blake's major works as I read (or re-read) them, but today I want to start with The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. Primarily I just want to get across some of the ideas he expressed in this work, even just as summary, but I will also give some commentary. You should be warned that some of the commentary will be comparisons of Blake to me more than any kind of real analysis of the work--which might suck for you if you don't know who I am… or if you do know who I am. I'm not sure which is worse.

(Special note: when I quote Blake throughout this post, I have chosen to correct his crazy spellings, capitalizations, and punctuation to more or less "smooth out" his writing for the sake of readability.)

You can and should read the entire Marriage of Heaven and Hell here first. It has both the text of the work as well as his illuminations. And, if you're interested in an analysis of the book, you can read a "run-through" I wrote for my world literature class this semester. The PDF is here.