You can read a version of the trickster cycle here, though I recommend picking up a book by Paul Radin called The Trickster: A Study in American Indian Mythology. It's got a better translation, is cleaner, and has commentaries and background by Radin as well as an essay by Carl Jung.

It was only a few years ago that I discovered this version of the trickster, when I decided to teach Native American myth in my world literature class. I knew about other tricksters, of course (even if I didn't call them that). Any character who breaks rules, plays jokes, shifts shapes, and turns things on their heads can be considered tricksters, including Brer Rabbit, Woody Woodpecker, and Bugs Bunny. I also knew about some of the more purely mythological tricksters like the ones found in Gilgamesh and Popul Vuh (another work that really appeals to me that I may talk about in a future post). Tricksters in general appeal to me, but none as much as the Winnebago (or Hotcâk) version, the one they call Wakdjunkaga ("the tricky one" or, more mysteriously and appropriately circular, "the one who acts like Wakdjunkaga").

The Trickster is a character who is sent by the Earthmaker to help humans, but he ends up going off on his own to do what he wants. The Christian tradition would probably call a character like this a devil, someone who rebels against the one who created him, usually because he wants to be independent. But the Winnebago didn't think of him that way. They thought of him as being foolish, but loveable, and also worthy of a certain kind of respect (he is a god, after all) and certainly important to their stories and their lives.

Here are just a few of the Trickster's adventures:

He begins his story by becoming a tribal chief who does everything wrong, blaspheming all of the Winnebago traditions. He then makes one of his arms angry at the other and begins cutting himself. He borrows two children from a friend and kills them through neglect. He mistakes a tree stump with a protruding branch for a man pointing at him and they have a pointing contest (a model for the "tar baby" story in Brer Rabbit).

He kills some ducks and tells his anus to guard them while he sleeps. Some foxes appear and Trickster's anus attempts to ward them off by farting, but they steal the ducks anyway. When Trickster wakes up, he is so upset at his anus for not properly guarding that he stabs it with a hot stick, causing his intestines to fall on the ground which he finds and eats. To heal his anus, Trickster ties it together tightly so that it wrinkles, which is why our butt-holes look the way they do today.

Trickster wakes up with an erect penis and thinks that the covers at the end flapping in the wind is the chief's banner, but he eventually gets his blanket back, coils up his penis, and puts it in a box he carries on his back (his penis box). He sees naked women in a lake and sends his penis across the water. It finds the chief's daughter and begins having sex with her. Her friends try to get the penis out, but can't. They call strong men who can't remove it either. Finally an old woman pries it out with an awl, throwing her backward several feet. Trickster responds, "Hey, I was fucking that girl!"

Trickster and his friends eventually decide to live the life of luxury by marrying the chief's son, so trickster makes breasts out of elk's kidneys and a vulva out of an elk's liver and puts a dress on. He marries the guy, and the Trickster gets pregnant and has three boys. But the jig is up when his fake vulva falls out.

He then takes the opportunity to visit his real wife and son, but gets bored and leaves. This is when he hears a voice that says, "If you eat me, you will shit." He finds that it is a talking bulb on a bush. He wants to prove the bulb wrong, so he eats it. He immediately begins farting, so much and so hard that his ass starts hurting. He farts so forcefully that it picks him up and pushes him forward like a jet-pack. Another time he is shot straight up into the air and he grabs a tree to stop himself and pulls it up at the roots. "At least I'm not shitting," the Trickster says. But then he begins doing that too, so much that he has to climb a tree because it keeps piling up under his ass and hitting his body. He eventually falls into his mountain of crap.

Later, a hawk flies into the Trickster's ass to teach him a lesson, but Trickster closes up his butt-hole so tight that the hawk can't get out. A chipmunk chews off part of Trickster's penis and testicles, which is why our penises are so small now, but also where we get lily-pads from (since that's what happened to the discarded parts). That's also where we get potatoes, turnips, rice, and other good things.

Eventually, Trickster does finally do some good for humanity around the Mississippi River area, and you can still see his butt and balls print on a rock where he had his last meal on earth.

My students are naturally confused by the stories. What is Trickster? A human, a god, an animal? Is he a man or a woman? How can he get pregnant if he has only a fake vagina? Do his ass and penis really have a mind of their own? Are we supposed to take the origin stories seriously? Why so much farting and pooping? And sex? And, most importantly, why is there so much comedy in a religious text?

I essentially tell them that if they can embrace all of the above mysteries that they will be better humans. We are so uptight. We like "yes" and "no." Thank God for Bugs Bunny (and similar characters, usually found in cartoons), because the religions we're most familiar with don't offer much comedy. Even the Trickster himself was hijacked by Christians; the Christian-influenced Peyote tribe would use him for morals ("Don't be like the foolish Trickster," etc.), as if he were just a "Mr. Bungle" from a 1950s education film.

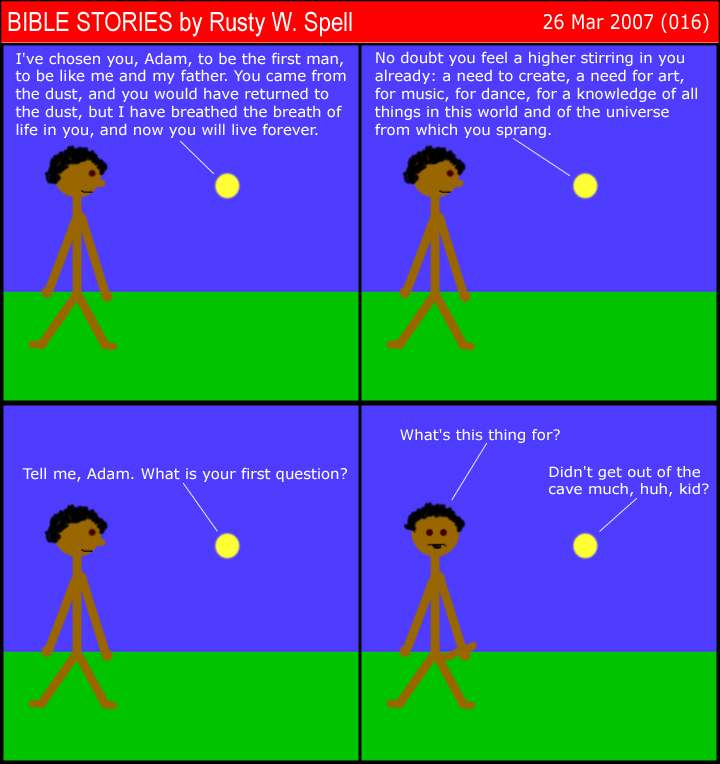

Do we watch Bugs Bunny to learn a moral? Are we confused when he dresses as a woman and seduces Elmer Fudd? Does it bother us that he's a rabbit and human (and more) at the same time? No, I hope not. If Bugs were part of our religions, we'd have better ones. Instead, we have a separation of church and comedy (if not always state). (As a side note, I don't think we should always be learning morals or lessons from the Bible either. As I said in the last post, there's a lot more going on than can be summed up in some Aesop's Fables style sentence.)

Two of the most powerful and downright magical things humans can do: (1) have sex and (2) laugh. The Trickster has both of these in abundance. This is why it speaks to me more than the Bible does. In spite of the fact that I'm making a comic out of the Bible, it's just not that funny. It has lots of sex, but (with the exception of the Song of Solomon) the sex is usually just violence or oppression in disguise. Presumably, religious texts are for humans, but it doesn't always seem like it. The Winnebago Trickster Cycle is definitely for humans.

The first part of the Trickster Cycle begins with this sentence: "Once upon a time there was a village in which lived a chief [the Trickster] who was just preparing to go on the warpath." This is only important (and funny) when we realize that a chief never went on the warpath. Later Trickster is found having sex, something forbidden to those going on the warpath. You can see the complications piling up, and they continue to for pages. The jokes begin eating themselves in paradoxical form. The Winnebago (rightly) felt that it was important to poke fun at their most sacred and profound customs and traditions.

To demonstrate an equivalent, imagine a Christian pastor at the beginning of a story sitting in the congregation waiting for church to begin (instead of starting it himself at the pulpit). He's stacked clumps of his feces and cups of his urine on the communion table, explaining that the body and blood of Christ has passed through to the other side from the previous communion. And so on (except tons more funny).

Many would just be offended, but that's where our religions fail. The funniest jokes should be those poking fun at the things you care the most about. This is why it's an honor to be roasted. One of our most ingrained concepts is the concepts of blasphemy (as a negative), but the Trickster Cycle asks us to embrace blasphemy. Blasphemy can be funny, and God can take it. The things we treat as holy (such as communion) are just symbols, and symbols are silly (and dangerous) if taken too seriously, and so to arrive at a stronger version of what those symbols can do for you, the entryway to this larger world is blasphemy, parody, and laughter itself. I'm totally serious, folks.

So if you read only the Bible for your spiritual edification, make sure you're supplementing it with one or more of the following cartoons that offer trickster-style releases necessary for fully-functional humans: Bugs Bunny and the rest of the Warner Brothers cartoons, Beavis and Butt-Head, or Ren and Stimpy. Tom Green is also a good solution.

No comments:

Post a Comment