I first read William Blake in high school when I was about sixteen years old: Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience. I liked those, but I started really liking Blake when I chose to do my eleventh grade research paper on his life and works. The more I found out about him, the more weirdly familiar he seemed to me, until I eventually started flattering myself with the thought that I must have been William Blake in a previous life (something that still crosses my mind each time I read him).

I first read William Blake in high school when I was about sixteen years old: Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience. I liked those, but I started really liking Blake when I chose to do my eleventh grade research paper on his life and works. The more I found out about him, the more weirdly familiar he seemed to me, until I eventually started flattering myself with the thought that I must have been William Blake in a previous life (something that still crosses my mind each time I read him).I was intrigued by Blake as a mystic, his having visions of his dead brother and of angels, of staring at a knot in a piece of wood until he became scared of it, etc. I've never had strong visions or dreams about anything (unless you count my occasional sleep paralysis), but I like the concept of seeing things that aren't there--or specifically, seeing differently the things that are there. I think I do this different-seeing a little, though sometimes I simply see nothing where everyone else sees something. Lots of this world is invisible to me.

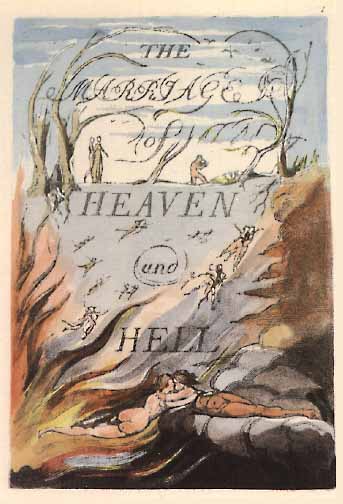

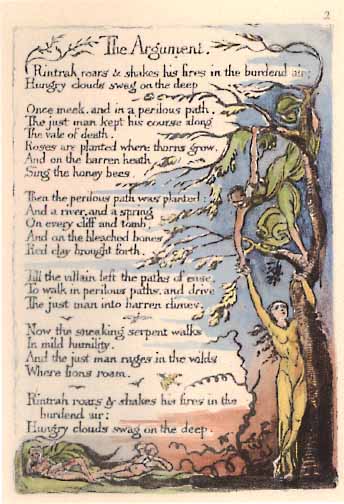

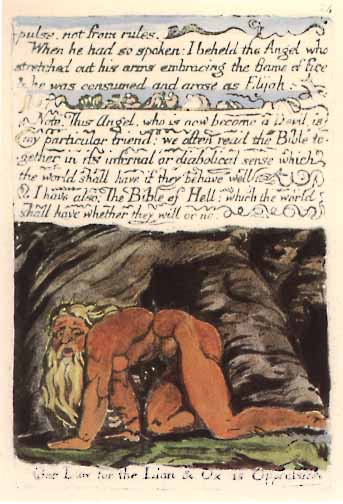

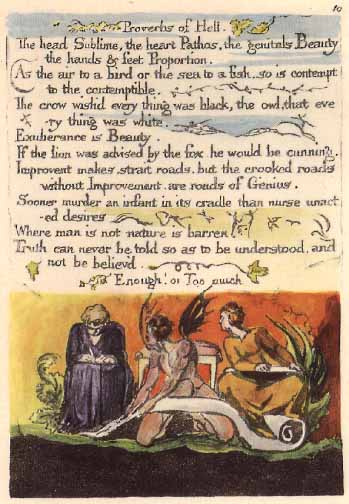

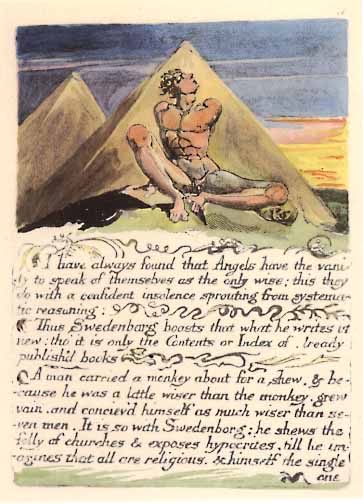

I was also intrigued by Blake as a visual artist. He was just as much a drawer, painter, engraver, etc. as he was a writer, and I loved the way he combined the two on the same page (or, in his case, engraved plate). This is how I got my start as a writer, too: writing words to tell stories about my pictures (and not the other way around). Like a lot of my favorite storytellers (C.S. Lewis and David Lynch to name two), the images came first. He also produced everything himself, rather than going to a traditional publisher, creating his books indie rock style, which is way that I've approached most of my art (especially my music), often from necessity but also because I like the freedom.

I became especially interested in Blake's prophetic books, though I didn't begin reading them properly until recently. As a teenager, I liked reading about them, but I must have felt (after glancing at the works themselves) that they were too much to undertake at that young age, so I put them off until later. Every time I read them now, that familiarity hits me again. They get me excited, and they also make me laugh.

I will probably eventually create posts for most of Blake's major works as I read (or re-read) them, but today I want to start with The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. Primarily I just want to get across some of the ideas he expressed in this work, even just as summary, but I will also give some commentary. You should be warned that some of the commentary will be comparisons of Blake to me more than any kind of real analysis of the work--which might suck for you if you don't know who I am… or if you do know who I am. I'm not sure which is worse.

(Special note: when I quote Blake throughout this post, I have chosen to correct his crazy spellings, capitalizations, and punctuation to more or less "smooth out" his writing for the sake of readability.)

You can and should read the entire Marriage of Heaven and Hell here first. It has both the text of the work as well as his illuminations. And, if you're interested in an analysis of the book, you can read a "run-through" I wrote for my world literature class this semester. The PDF is here.

One of the things that I love about The Marriage of Heaven and Hell is that, although it doesn't look like it at first glance, it's both a parody and a satire. As I said in my Trickster post, comedy should be a part of any meaningful connection with God. My favorite parodies are not necessarily the ones that "make fun" of something, but the ones that are more or less loving tributes. The music of Ween, Tenacious D, Liam Lynch, and 'nikcuS comes to mind. And this is what Blake is doing in lots of the Marriage. He begins with a parody of the book of Isaiah. Again, he's not "making fun" of Isaiah, but he's using the Biblical language in order to (a) give his words extra built-in power and authority and (b) to be funny. So it's a parody, but it's a serious parody (like Hamlet).

One of the things that I love about The Marriage of Heaven and Hell is that, although it doesn't look like it at first glance, it's both a parody and a satire. As I said in my Trickster post, comedy should be a part of any meaningful connection with God. My favorite parodies are not necessarily the ones that "make fun" of something, but the ones that are more or less loving tributes. The music of Ween, Tenacious D, Liam Lynch, and 'nikcuS comes to mind. And this is what Blake is doing in lots of the Marriage. He begins with a parody of the book of Isaiah. Again, he's not "making fun" of Isaiah, but he's using the Biblical language in order to (a) give his words extra built-in power and authority and (b) to be funny. So it's a parody, but it's a serious parody (like Hamlet).The entire thing isn't using the voice of Isaiah, however, and lots of it is just downright plainspoken (which is also funny). Throughout the entire piece, however, is a perfect combination of comedy and seriousness, self-importance and self-depreciation, sacred and profane. This fits perfectly with one of Blake's initial statements: "Without contraries is no progression." That's the purpose of the "marriage" of Heaven and Hell. Religion almost always separates. Religion (for one) says that the soul (or mind) is separate from the body, that the soul is good while the body is evil, that passive people will go to Heaven while active people will go to Hell. Blake thinks that this kind of dualism is death. To say that Blake wants to "combine" these elements is only partially true, since the real truth is that he doesn't see them as separate at all. They are simply bogus distinctions.

Think of how much of religion is based around the idea that the body is evil. The idea of the "Virgin Mary" is crucial to most of Christianity. Jesus was only able to finish the job by having his body destroyed. The Da Vinci Code controversy (as well as the older Last Temptation of Christ controversy) is based around the for-some-reason-scandalous idea that Jesus may have had sex (or at least thought about it). Abstinence education is more of a religious movement than anything else. And this is just the sexual component of the body. (Fasting and avoiding gluttony was once another religious way of avoiding temptation, but this has largely gone out the window in America. We traded "free love" for obesity, it seems, but that's another post.)

"As the caterpillar chooses the fairest leaves to lay her eggs on, so the priest lays his curse on the fairest joys."

Throughout my early life, I was taught by religion that the body was bad news. Sometimes the body was stifled so much that sex was something too far in the distance to even discuss. At least we had the outlet of doing things "in the spirit." I might go into this in a later post, but I was raised in a pretty physical church. You could dance in the spirit, sing in the spirit, and generally do anything that was fun as long as it was "in the spirit." But woe unto those who did these things out of the spirit. Dancing in a club on a Friday night, singing ABBA songs at a karaoke: all of this was bad. To a kid, of course, and often to an adult, the distinction was difficult to discern. Luckily, my family and I were rebellious enough that we didn't care, so I sang and danced to Alvin and the Chipmunks all I wanted while my folks did the Twist guilt-free.

Throughout my early life, I was taught by religion that the body was bad news. Sometimes the body was stifled so much that sex was something too far in the distance to even discuss. At least we had the outlet of doing things "in the spirit." I might go into this in a later post, but I was raised in a pretty physical church. You could dance in the spirit, sing in the spirit, and generally do anything that was fun as long as it was "in the spirit." But woe unto those who did these things out of the spirit. Dancing in a club on a Friday night, singing ABBA songs at a karaoke: all of this was bad. To a kid, of course, and often to an adult, the distinction was difficult to discern. Luckily, my family and I were rebellious enough that we didn't care, so I sang and danced to Alvin and the Chipmunks all I wanted while my folks did the Twist guilt-free.It sometimes seemed that the ideal state was to be some kind of floating cloud of invisible thought. The Age of Enlightenment was a great leap ahead from an age of the blind following of religious authority, but in some religion in America these days, it seems that we have the worst of both ages. We can't love our bodies or use our brains.

Part of the premise of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell is that Blake is going against the common thought of his age (the tail end of the Age of Enlightenment), which makes him a devil. So all the positive (for lack of a better term) characters in the Marriage are devils, while the negative characters are angels. The fun, glorious places are Hell, while the stifling places are Heaven. This isn't reversal for reversal's sake. Remember that these good/bad distinctions are silly to Blake to begin with. Instead, he's adopting these dualist terms to make his points.

We do the same thing ourselves all the time in conversation. We say "Man, I know I'm going to hell" while laughing, or we call ourselves or others devils because of some fairly harmless behavior (that nonetheless offends others). And we sarcastically call self-righteous people "little angels." And if you go just an inch or two away from the norm, you run the risk of being called a devil. Even someone who has a God blog might be under attack for being a godless heathen.

Hell, by the way, as a place for eternal punishment, was an offensive idea to Blake, and it always has been to me. Even as a child, hellfire preaching smelled to me like desperate fear tactics. "If you don't want to worship God because you love him, then consider that you might be burned and stabbed with a pitchfork." Images of Heaven were equally silly to me, even some of the more metaphorical ones. All of the images appealed to either our materialistic, need-for-comfort natures (Heaven) or to our fears of pain (Hell). The whole thing felt like a parent offering a kid ten bucks if they make all As and a spanking if they didn't, rather than stressing the innate goodness of doing well in school.

Anyway, William Blake is using the same kind of "ain't I a devil?" jokes we do, but -- once again -- he's being more serious about it, since at the core of some of these jokes are grave issues such as the American and French Revolutions, slavery, oppression of the poor, the suppression of creativity, repressive theology, etc. So, using the voice of the devil, Blake launches into a direct attack on these oppressive thoughts arising from religion, politics, and more.

Blake is able to explain how religion comes about in only one page of writing. He says that once upon a time, artists would take common elements -- woods, rivers, mountains, lakes, cities, nations, etc. -- and assign a god to them. So we have wood gods or river gods or a statue put in the middle of a town that is meant to represent the spirit of the city. Only art and poetry can properly describe God, and that's what was happening here. However, literal-minded, boring priests came in and actualized these poetic images and forced people to worship the images, eventually claiming that it was the gods themselves that did the forcing. In this way, Blake explains, "men forget that all deities reside in the human breast."

Blake is able to explain how religion comes about in only one page of writing. He says that once upon a time, artists would take common elements -- woods, rivers, mountains, lakes, cities, nations, etc. -- and assign a god to them. So we have wood gods or river gods or a statue put in the middle of a town that is meant to represent the spirit of the city. Only art and poetry can properly describe God, and that's what was happening here. However, literal-minded, boring priests came in and actualized these poetic images and forced people to worship the images, eventually claiming that it was the gods themselves that did the forcing. In this way, Blake explains, "men forget that all deities reside in the human breast."I always think it's stupid when people say that believing in God is like believing in fairy tales. For one thing, I don't like fairy tales being put down as something silly. But I do understand the point of this statement, and Blake says what these people are trying to say in a better way when he says that priests are "choosing forms of worship from poetic tales." God is all of these poetic tales put together, not just one. The problem lies in first separating whole things into parts and then choosing only one of those parts that you feel is the best. In doing so, you're only getting a small portion of God; as a result, you're actually not getting God at all. It would be like having a conversation with my clipped toenail and then pretending you've met me.

As an illustration of this in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Blake imagines that he is speaking with the prophets Isaiah and Ezekiel. They explain to him that their prophecies, more than anything, were trying to turn people away from these narrow gods and to tell people about the true God, which they call "Poetic Genius." They explain that prophecy isn't hearing God in an audible voice or seeing him in a physical way. Instead, they "discovered the infinite in everything" and wrote what they felt. Of course, the prophets lament, everyone enjoyed so much what they said that they wanted to worship their god exclusively, missing the point. Creativity was once again replaced with specific gods and rules, and the cycle continued.

It's refreshing to think of the prophets in this way, that they're not out to convert you to one god. On the contrary. They're not playing religious football, rooting for the winning deity. As a simplified illustration, think of it this way. Imagine someone says, "When I come to this art museum, it feels like I am with God." As a result of hearing this, someone else starts worshipping the art museum itself. This is the basic concept of idolatry, but not in the basic understanding of it as "statue-worship." In William Blake's version of idolatry, worshiping the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob -- or worshipping Jesus -- is also idolatry. You're choosing one element of the infinite and putting all of your attention onto it alone. You're worshipping God's clipped toenail.

In the final parts of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Blake tells us that worshipping God has nothing to do with going to church, praying, or anything like that. He says that worshipping God is honoring what is creative, great, and valuable in each other. Jesus said almost as much when he says that whatever you do for "the least of these," you do for him.

In the final parts of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Blake tells us that worshipping God has nothing to do with going to church, praying, or anything like that. He says that worshipping God is honoring what is creative, great, and valuable in each other. Jesus said almost as much when he says that whatever you do for "the least of these," you do for him.There's a large comparison to be made between Blake's ideas and what Jesus was preaching--more than I'm willing to write about now, but basically Jesus was telling everyone that he was God and was more or less telling everyone else that they could be God, too. Remember, "all deities reside in the human breast." Blake points out in the Marriage that Jesus went around breaking all of the commandments and says that "no virtue can exist without breaking these ten commandments." Think of what Jesus constantly got in trouble for: not following rules, not following religion, claiming he was God… you know, being a devil.

And, most importantly to Blake, Jesus was being his own person, creative and original. William Blake prizes creativity more than anything. Sometimes creativity looks foolish, but Blake says that "if the fool would persist in his folly, he would become wise." Anything anyone's ever done worth remembering or repeating is something that maybe began as something seemingly foolish, and it certainly began as an idea, a bit of creativity. Someone attempted something new and the world was changed, in a small way or in an immeasurable way.

I recently realized that anything I care about in the world can be reduced to two things: creativity and love (and maybe just creativity). As this pertains to God, you'll notice that he seems to mostly appear in one form of art or another: literature, music, dance, paintings, films, sculpture, architecture, etc. Even church is a piece of theatrics, sometimes called "the art of worship." Prayer is soliloquy. I don't think it's an exaggeration, or a reduction, to say that God is art, or "Poetic Genius."

William Blake's ideas, too, might sound foolish. To some he's simply a weirdo mystic. But you can see how our world would improve overnight if we were able to sincerely put his ideas into practice. We'd go one better than the golden rule of treating each other like we want to be treated; we'd treat each other like we'd want to treat God. We'd stop arguing over whose deity has the biggest dick, which would reduce tons of wars and even infighting amongst the religious. We wouldn't blindly follow rules simply because they're "holy." We'd stop thinking of our bodies as being lowly, and we'd realize that it and the mind work together. We'd be able to discard any shackles of oppression, in all of its forms. We'd value the best and most creative ideas, squash the mediocre ones, and throw out anything that simply isn't working anymore. We would know that every good idea we have, and every application of that good idea, is a godly expression, better than any prayer. We wouldn't even have to use the word god anymore if we didn't want to, and morality would have meaning beyond religious rules and restrictive images. We'd be able to discover the infinite in everything.

Of course, if I actually am the reincarnation of William Blake, I'm sure it sounds like I'm just tooting my own horn. At least it's a prophetic horn.

14 comments:

I read your comic a while back and I just found it again today. When I'd caught up I started clicking around the site and found the blog. This is the only post I've read so far, but I've fallen in love with your ideas. :) Keep up the good work. I'll keep reading.

Thanks a bunch. I don't get to write as many entries here as I'd like, but nice comments like these encourage me to keep at it.

Lovely post, Rusty. I've been extravagantly interest in WB for about 25 years. I gather you and I have a lot in common. I mean to spend more time on your blog; I've just started a "new" blog at http://ramhornd.blogspot.com/,

hoping to interest people in blake. Love for you to visit me there or at

lclay3.50webs.com/blake/primer.htm.

I especially enjoyed one of your blogs on church.

Thanks, Larry. I took a look at your new blog and like it. I'll check in and maybe leave some comments. Your other site is enormous and good; I'll be sure to reference it next time I choose to write about Blake.

I've been looking for something to help me get a good grasp on what this work of Blake's means for a while now. Thanks for helping a struggling English major pass an exam. :)

Brittany, glad I could help. If you wanna read Blake himself explaining some of these concepts in a more simplified (for him) way, try his *All Religions Are One*.

Hello! I just thought I'd tell you how much I enjoyed this posting. It helped me understand the writings of Blake more than I can express. I read it over several times, actually! :)

Wow, two thank-yous in two days. Makes me glad I wrote this post a year and a half ago. Glad you enjoyed it. (Hope you looked at the PDF also.)

Your analysis of Blake's work is the only reason why I'll understand my 300 level English lecture tomorrow. Not even Sparknotes taught me as much as your PDF did. THANK YOU

Glad to help, Anonymous.

A good post. Blake had an amazing imagination, and was extremely gifted as a painter Great drawings too. His work seems very ahead of its time.

Thanks for the post.

Thanks for the comment, Tanya. I agree.

You truly have extracted the essence of Blake's this work, I read his poem and was wondering what actually he wanted to say, and believe me it really helped me a lot.Keep on writing. Thanks.

Thanks, Harvindar. Glad I could help.

Post a Comment